|

Longstreet at Antietam : Profile of a

Commander

Nicholas E. Hollis

(All Rights Reserved)

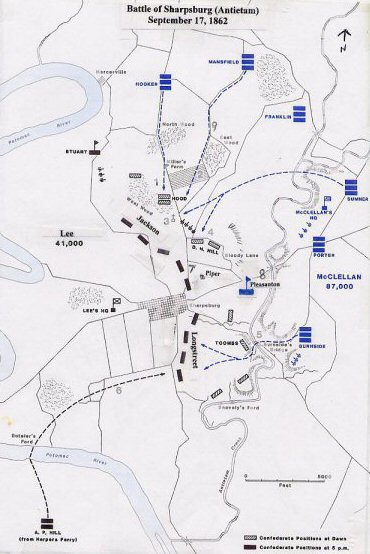

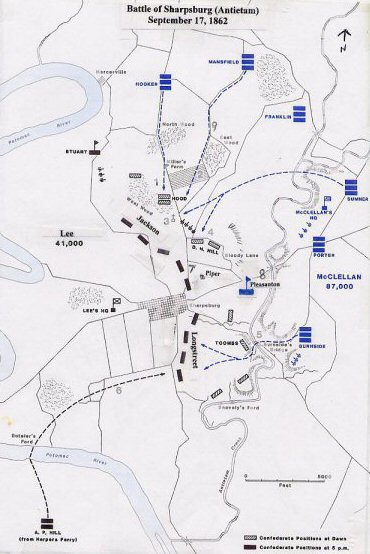

The Battle of Sharpsburg (Antietam) marked

the end of CSA General Robert E. Lee’s first invasion of Maryland

(September 1862). The epic clash pitted a heavily outnumbered Army of

Northern Virginia (ANV) of 41,000—arrayed in strong defensive

position—against the Union Army of the Potomac (AP) of nearly 87,000 under

the command of Major General George McClellan.

Cornered with his back against the Potomac

River, Lee had turned his army to face the pursuing Federals, positioning

the ANV’s first corps on the right/center under Major General James

Longstreet on the hills above Sharpsburg and Antietam Creek, with ANV’s

Second Corps, under Major General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, on the left

across Hagerstown Pike, partially concealed by woods near a cornfield and

an old German church. ANV’s cavalry, under Major General J.E.B. Stuart,

held the far left.

Deadly September Showdown

The bloodiest day in America

history (September 17) began with furious, yet uncoordinated Union attacks

on the ANV left. The Union First Corps under General “Fighting Joe”

Hooker, delivered the initial assault at dawn, pushing Jackson’s brigades

back, but then stalled as ANV Major General John Bell Hood’s Texas

brigades counterattacked savagely (1). The AP Twelfth Corps under Major

General Joseph Mansfield attacked next through a cornfield at 7:30 a.m.,

capturing the Dunkard Church (2) — followed by a third massive Union drive

led by Major General Edwin Sumner’s Second Corps which slammed into the

struggle around Dunkard Church (3) and also pummeled the center of the ANV

line held by General D.H. Hill’s division along a sunken road (4) several

hundred yards away from Longstreet’s headquarters at Piper House.

Although there were many heroics on the

field on both sides, climaxed by the late afternoon arrival of A.P. Hill’s

brigades from Harper’s Ferry (6) in time to flank and check a broad Union

offensive on the right led by Union General Ambrose Burnside (5), the

actions of James Longstreet at the center deserve special attention. Lee

certainly thought so. As dusk settled on the bloody stalemate, and his

unit commanders gathered to assess their precarious situation, Lee saw the

melancholy and fatigue of near defeat in their eyes. But when Longstreet

rode up, Lee approached him as he dismounted , and with apparent

exuberance, clasped his shoulders with his hands, exclaiming “Ah, here is

General Longstreet, my old war horse. Let us hear what he has to say”.

A Thin Gray Line

In fact, Old Pete’s rugged

courage and steady performance at the front that day was the stuff of

legends. At the center of the rebel position, during the apex of Sumner’s

assault, Longstreet observed General Richardson’s division (AP) swinging

his line up along the crest of the hill (7) overlooking Piper House

(Longstreet’s field headquarters). The advance threatened to divide the

ANV’s position and rout the Confederates. But as the Federals swarmed over

“Bloody Lane”, moving toward the higher ground, Longstreet used his

presence to inspire his men and bolster the firing line, ordering his

staff officers to man an artillery battery and fire canister into the

advancing Federals. The rebel line was only fragmentary, but with shells

bursting around him, Old Pete calmly held the reins of his men's horses,

while surveying the desperate situation with his field glasses. He

remained mounted, if somewhat inelegant—with a slipper on an injured

foot—but his men were awestruck at his confident, imperturbable demeanor.

Moxley Sorrel, an aide, called him “magnificent”. When pressed by one of

his subordinates for help, Longstreet penned a short note,

“ I am sending you

the guns, dear General (Pryor). This

is a hard fight, and we had best all die than

lose it.”

|

(Photo courtesy of Paul Breitenbach) |

BLOODY

LANE--Rebel troops held off Federal attacks for nearly three and a

half hours along this sunken road, before being dislodged by B-G

Israel B. Richardson’s division.

|

The Fog of Battle

For the Union commanders facing

the ANV center there was no way to determine the depth of Confederate

troop strength behind the crest of the rolling hills. Could it be another

death trap like the Battle of Second Manassas a few weeks before or even

the as the West Woods had become earlier that same day? Union Cavalry

General Alfred Pleasanton (8) had orders to reinforce Richardson’s assault

and General Porter’s Fifth Corps was readied to deliver a crushing blow.

But the attack never came. Longstreet’s canisters and a demonstration move

by D.H. Hill fooled a Union command already in some disarray after both

Richardson, and his gallant Colonel Francis Barlow of New York, fell in

quick succession leading the advance.

Earlier that morning General Pleasanton had

dispatched one of his mounted companies (12th Pennsylvania)

under Major James A. Congdon, forward to the far right of the Union line

to monitor their rebel counterparts under Stuart. The detached unit was

posted off Hagerstown Pike (see diagram) on Poffenberger Lane (9) near the

East Woods for “provost duty” (herding stragglers, guarding prisoners) At

this position Congdon’s men, including

Pvt. Calvin W. Jennings, a nineteen

year old farm boy with a bugle, witnessed the carnage of the cornfield –

some of the heaviest fighting of the war. Thousands fell in the neat rows

of blood spattered corn, and whole units were practically decimated with

neither side holding clear advantage.

|

Sources: National Park Service/Antietam -- Unit

Placement. William J. Clipson--Cartography.

|

A Captured Battle Flag

At one point after fresh Ohio

units slammed into the 6th and 27th Georgia

regiments, and the 4th Texas of General Hood’s division, Major

Congdon stopped and questioned an enlisted soldier carrying a captured

rebel battle flag toward the rear. When the flag’s identity could not be

determined, Congdon asked one of his new prisoners, Lt. William E. Barry

of G Company, 4th Texas, if he knew the flag. With great

emotion, Barry told his captors that the flag belonged to the First

Texas—a unit which had sustained heavy casualties, losing 182 out of 226

actives within a few minutes.2/

As bugler, posted near his commander,

Calvin Jennings probably witnessed the poignant moment, aware that some of

his Jennings relatives were fighting under ANV banners.

|

VIEW FROM

EAST WOODS--Union troops could glimpse the battle, across the

cornfields and the West Woods. This present day photo looking west

from Poffenberger Lane near spot where the Twelfth Pennsylvania

Cavalry was posted on the morning of September 17, 1862.

|

Aftermath

Lee retreated across the Potomac into Virginia the following

night, his Maryland gamble lost, and later President Abraham Lincoln

sacked General McClellan for failing to press the attack. Lincoln would

also use Antietam to promulgate the Emancipation Proclamation giving new

inspiration to the Union cause. In Richmond, the near disaster of the

Maryland campaign prompted a reorganization of the Confederate army. Lee

remained in firm command, but on October 9, 1862 he chose Longstreet as

his chief lieutenant, elevating him to Lt. General of the ANV’s First

Corps. The next day commissions were signed for six other generals, ranked

as lieutenant generals, including Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, who was

placed in command of ANV’s Second Corps.

Antietam proved decisive

in other ways. Southern momentum, generated from a string of victories,

including Second Manassas in late August, was checked – and the potential

of foreign diplomatic recognition for the Confederacy as a sovereign

nation (likely with a CSA victory) faded. The sheer carnage of America’s

deadliest day had a profound impact on the country’s psyche – particularly

after Matthew Brady’s photographs became public. More than 3,650 Americans

had been killed on that September day in 1862 (2,100 Union, 1,550 CSA),

with over 17,000 wounded. A hundred forty years later, after the horrors

of September 11, 2001, comparisons would be made between Antietam, Pearl

Harbor, Omaha Beach (Normandy), and the World Trade Center towers.. But

the Battle of Sharpsburg stands apart with searing impact, as it reflected

the mounting losses of the larger Civil War – a tragic “family dispute”

out of control, with brothers-in-arms warring on each other, whose long

shadow still haunts us today.

Notes and Additional

Reading

1/Landscape

Turned Red: Battle of Antietam, Stephen Sears, (1983,) p.272

2/Antietam:

A Soldiers’ Battle, John Michael Priest, (1989), p. 89

Leather and Steel: The

12th Pennsylvania Cavalry in the Civil War, Larry B. Maier,

(2001)

The Gleam of Bayonets:

The Battle of Antietam and Robert E. Lee’s Maryland Campaign, September

1862, James V. Murfin, (1965)

Manassas to

Appomattox, James Longstreet, (1895), p.250-252 |